On Holding Your Mouth Right — A Way of Writing

You have to hold your mouth right. It’s what my dad said when we fished. The fish won’t bite unless you do. And if one of us didn’t catch any, “Guess you weren’t holding your mouth right.” No one ever said what “right” meant, and of course we didn’t ask. It was another adult thing that we were supposed to intuit or figure out. Holding your mouth right means closed, as in No Talking. That much was clear.

I experimented with pursing my lips, the way fish lips looked to me, then held my mouth at a slant, one side lower than the other, like a fish’s grimace when you dragged it out of the water. I couldn’t tell that either one helped any, but getting still enough tot try these out, I noticed things. Movements at the surface of the pond and where the deeper water seemed to start. Half-submerged logs and branches we called “stick-up’s” near Dad’s red and white bobber. I slid my line closer to his.

Focused on how I held my mouth, I was too busy to pull my line out every minute or two to see if I had caught anything. All of which made catching a fish more likely. Working out the puzzle of how to hold my mouth, I forgot to be anxious.

It occurs to me that I can apply the same strategy to writing — especially in this time when the words are slow to bite. If I hold my mouth just right, I might notice where the water shifts hues and dip my a line into a deeper spot, attend to that edge where shallow mets deep. There’s often food for thought there. And perhaps I’ll look more closely at what’s pushing through the surface — “stick-up’s” and menacing logs I’ve avoided approaching in words.

How does a writer hold her mouth? closed? pursed? askew? Does she bite the tip of her tongue, lick her lips? All of the above — and more. The writer mostly allows her mouth to rest at its ease as she listens to street sounds, to the person across from her or the one behind her in line, to the wind between branches or buildings, to a remembered voice still alive in her somewhere. And especially to children — or anyone — speaking in language fresh and mysterious as words are to her when they first start to bite, when the tug of their life at the end of her line is almost more of delight and deep joy than she can land.

Engaged this trail of thoughts, I don’t put the pen down every five minutes, convinced I can’t write anything that matters. Trying to figure out how a writer holds her mouth takes my mind off the need to produce a first draft worthy of the effort, as if all first drafts aren’t meant to be returned to the water to grow a while.

On the bank of that pond I once pulled up a sleek bass. Iridescent as it came free of green water, the fish bowed its length to a furious arc, stippled and streaked blue-gray-jade, fierce as fire. I pulled the bass close, lifted it from the hook with a light hand. I slipped it back into the bright patch of sky caught in the pond and took myself home in the dusk.

Author’s note: Writing this post made me go looking for William Stafford’s essay, “A Way of Writing” (from Writing the Australian Crawl.) I remembered that Stafford compared his daily writing ritual to fishing. I’m glad I sought out the essay, which I had not read for years. It richly repaid my search. You can read it online here http://ualr.edu/rmburns/RB/staffort.html and more about Stafford and his work here http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/william-e-stafford

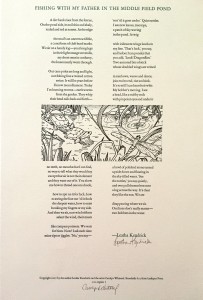

I’ve written about fishing before. Larkspur Press www.larkspurpress.com/ published one of my fishing poems, “Fishing with my Father in the Middle Field Pond,” as a broadside. Carolyn Whitesel did the gorgeous illustration.